Click on any of the following tabs to learn more about those topics.

Diabetes information

Diabetes medications

Diabetes technology

Optimising management

Diabetes complications

Diabetes support

Optimising diabetes management

In order to reduce your risk of developing diabetes-related complications it is important to optimise your diabetes management. Particularly if you have type 1 diabetes, it is important to improve your time in range, whilst minimising hypoglycaemia. The following articles will help you understand different aspects of diabetes management, relating to insulin treatment.

Time In Range

Research has shown that there are huge benefits of using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in people with diabetes, particularly for those with type 1

diabetes.

Whether you use CGM in combination with multiple daily injections (MDI) or with an insulin pump, if you use CGM regularly you can improve your day-to-day blood glucose levels (BGLs), your HbA1c (the 3-month average test for diabetes), reduce the risk of developing diabetes related complications and hypoglycaemia, all through monitoring your Time in Range.

What is Time in Range?

The Time in Range (TIR) is the percentage of time you spend with your sensor glucose (SG) levels in a particular target range. TIR can also be reflected as the hours per day spent in range. Time in Range includes three key CGM measurements:

1. TIR, which is the percentage of readings and time per day within the target glucose range

2. Time Below Range (TBR), which is the time spent below the target glucose range

3. Time Above Range (TAR), which is the time spent above target glucose range

The main goal is to increase the TIR whilst avoiding hypoglycaemia, or in other words, reducing the TBR.

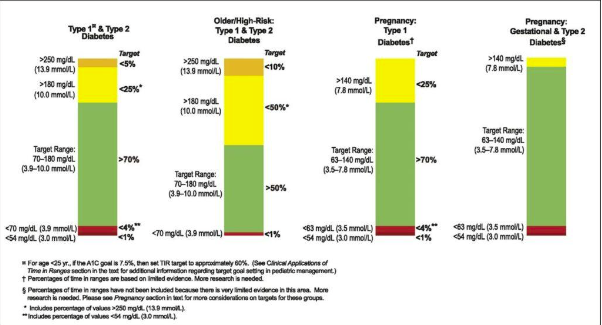

What is the optimal Time in Range target?

Most diabetes experts agree that a SG target range of 3.9-10.0 mmol/L is ideal. However special considerations, such as pregnancy or other health conditions, will need to be taken into account. Talk to your diabetes healthcare professional about what your personal target range should be.

For most people with diabetes it is recommended:

- To spend at least 70% of the day TIR (3.9-10.0 mmol/L)

- To spend less than 4% of the day in TBR (under 3.9 mmol/L)

- And less than 1% of the day under 3.0 mmol/L

- And, as a result, to spend less time in TAR (above 10.0 mmol/L)

Hypoglycaemia is an acute complication of diabetes and hence it is also important to look at both the time in range as well as the time below range.

Higher percentages of TIR, like lower HbA1c results, are associated with a decreased risk of the development of diabetes related complications.

How is TIR different from HbA1c?

Having said that, research shows that a TIR of 70% in most cases corresponds with a HbA1c of 7% (53 mmol/mol), whereas a TIR of 50% is correlated to a HbA1c of 8% (64 mmol/mol).

Similarly, an increase of TIR of 10% (which is equivalent to 2.4 hours per day more time spend in range) corresponds to a decrease in HbA1c of around 0.5% (5.0 mmol/mol). So, there is certainly a link between the 2 measures.

So why not stick with HbA1c, like we are used to?

In short, because HbA1c does not give any indication as to how much time you spent in hypoglycaemia. Let me clarify this statement with an example:

You can have a HbA1c of 7.0% with blood glucose levels between 4.0 and 8.0 mmol/L, but you can also have a HbA1c of 7.0% with BGLs between say 2.0 and 22.0 mmol/L.

Also, some medical conditions can affect the HbA1c measure, including conditions such as haemoglobinopathies (a range of conditions that affect haemoglobin), anaemia, iron deficiency and pregnancy.

And, HbA1c is a “weighted average of glucose levels”; this means that glucose levels in the past 30 days contribute considerably more to the level of HbA1c than do glucose levels from 90-120 days earlier. If you had big changes in your BGLs in the last month (such as often happens with special occasions or during holidays such as Christmas or Easter) this may have a significant impact on your HbA1c.

Limitations of only using TIR

CGM lets you observe changes in your glucose levels and daily profiles, including patterns of hypo- or hyperglycaemia and this can greatly assist you (and your diabetes healthcare professional) in making therapy decisions and any lifestyle changes.

However, when glucose levels are changing rapidly there may be a delay in the CGM registering the SG changes. This is also known as lag time (more on this later).

Also, CGM is not a “set and forget” system; it requires you (and your diabetes healthcare professional) to interpret the data and act upon this appropriately. You would need to actively use CGM for it to be effective and this can be costly.

How can I improve my TIR?

First, address any hypos you may be having. By avoiding hypoglycaemia, you will be able to reduce your TBR and often you will minimise rebound hyperglycaemia at the same time, which will reduce your TAR and hence improve your TIR. Talk to your diabetes healthcare professional for advice on how you can achieve this.

People with type 2 diabetes tend to have less variability in their glucose levels and tend to have less hypoglycaemia than those with type 1 diabetes, therefore people with type 2 diabetes can often achieve more TIR, more easily.

You can improve your TIR by counting carbohydrates actively and accurately, by adjusting your bolus (pre-meal) insulin doses based on your current SG or BG level, your glucose target, your insulin to carbohydrate ratio (ICR), insulin sensitivity factor (ISF), any insulin left on board (IOB) and your insulin action/duration.

When it comes to making insulin dose adjustments; slow and steady wins the race.

Physical activity and meal composition (the balance between carbohydrates, protein, fat, vitamins, minerals and fibre) of course also play a major role and need to be considered. When making changes to your insulin regimen, always follow the advice of your diabetes healthcare professional.

References:

1. Andrade Lima Gabbay et al, Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome, published 16 March 2020; Time in range: a new parameter to evaluate blood glucose control in patients with diabetes. https://dmsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13098-020-00529-z

2. Battelino et al, Diabetes Care, August 2019; Clinical Targets for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data Interpretation: Recommendations From the International Consensus on Time in Range. https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/42/8/1593

3. R. W. Becket al, J Diabetes Sci Technol. 13 January 2019; The relationships between time in range, hyperglycemia metrics, and HbA1c. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30636519/

4. R. A. Vigersky, C. McMahon, Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics, online 1 February 2019; The Relationship of Hemoglobin A1C to Time-in-Range

in Patients with Diabetes. https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/dia.2018.0310

5. T. Danne et al, Diabetes Care December 2017; International Consensus on Use of Continuous Glucose Monitoring. https://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/40/12/1631

Insulin Sensitivity Factor

The Insulin Sensitivity Factor (ISF), sometimes also called the Correction Factor, reflects the influence a unit of insulin has in your body. The ISF specifies how much 1 unit of rapid-acting insulin may drop your blood glucose level (BGL).

ISF can be used if you are on an insulin pump, or if you take Multiple Daily Injections (MDI) in the form of a basal-bolus insulin regimen (once or twice daily long-acting insulin and rapid-acting insulin before (main) meals). Let’s first look at calculating the ISF using MDI.

How is the ISF calculated?

One way of calculating the ISF is by using the scientifically evidenced ‘100-rule’.

First you need to calculate your Total Daily Dosage (TDD) by adding up both the rapid-acting (bolus or pre-meal insulin) and long-acting (basal or background) insulin doses in a 24-hour period. It will be more accurate if you calculate the TDD over a few days and take the average.

Then you take the number 100 and divide it by your current TDD to calculate the ISF.

For example: If you take 55 units of Optisulin at night and 8 units of Novorapid at breakfast, 6 units at lunch and 7 units at dinner your TDD will be:

55 + 8 + 6 + 7 = 76 units/day

100 : 76 = 1.3

This means that you will need 1.3 units insulin of rapid-acting to drop your BGL 1 mmol/L. In other words, your ISF is 1.3.

How do I use the ISF?

You can use the ISF to get back to target if your BGL is too high or too low through the following formula: current BGL – target BGL divided by ISF. Generally, the ISF is added to the insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR) at meal times and is based on the pre-meal BGL.

For example: If your BGL is 17.2 mmol/L and you have an ISF of 1:3 and a target BGL of 6.0 mmol/L it would mean that you would need around 8 units of rapid-acting insulin to get your BGL back to target:

17.2 – 6.0 = 11.2 and 11.2 : 1.3 = 8.6

To reduce the risk of hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose levels) it is recommended to round off downwards to the next nearest whole number, so in this case 8 rather than 9 units (or 8.5 if your pen device can deliver insulin in half unit increments).

If you are using a BG target range (for example BG target of 4.5-7.5 mmol/L) instead of a hard target of 6.0 mmol/L as in the example above) it is recommended to aim to decrease high BGLs using the ISF to the upper limit of the range (in this example: 7.5 mmol/L).

17.2 – 7.5 = 9.7 and 9.7 : 1.3 = 7.5, so you would take 7 units to correct.

BGLs below the target can be corrected using the ISF also, but in this case the insulin amount would be deducted. For example: if your BGL is 3.5 and your target BGL is 6.0 you would first treat the hypo with some quick-acting carbohydrate and would decrease your pre-meal bolus:

3.5 – 6.0 = -2.5 and -2.5 : 1.3 = -1.9, so you would decrease your pre-meal bolus by 2 units.

How do I know if my ISF is correct?

You should check your BGLs 2-3 hours after taking a correction bolus (or check your continuous or flash glucose monitoring data at those times) to check if your correction factor is right. If your BGL is to target then you know the ISF (and your carbohydrate counting and insulin to carbohydrate ratio or ICR) are correct.

If your BGL remains above target or you experience a low BGL 2-3 hours after that meal then the correction factor may need to be adjusted. Your endocrinologist or credentialled diabetes educator can help you with this.

Insulin resistance

Insulin resistance means that the insulin in your body does not work all that well, in other words, you are less sensitive to insulin and will need larger amounts of insulin to correct for high blood glucose levels. This means that you will have a lower ISF number, for example an ISF of 1.0 rather than 1:3 in our example above.

Insulin Resistance is increased by stress and weight gain. This means that you may need more insulin during these times and your ISF may need to be adjusted. In contrast, physical activity (in particular resistance training) will make you more sensitive to insulin and may increase your ISF during as well as after exercise. Always follow the advice of your healthcare professional if you are planning on making any insulin dose adjustments.

Check the basal first

Before calculating or changing the ISF it is important to check if your basal/background insulin (Toujeo, Optisulin or Levemir) dose is correct. You can do this by comparing your pre-bed BGL with your fasting BGL. If your FBGL is often more than 4mmol higher or lower than the night before you may need to change your basal insulin dose by 1-2 units (follow the directions of your diabetes HCP).

Whenever the basal insulin dosage is changed it is advisable to give it at least 3 days to see the new pattern before making any further changes.

ISF and insulin pumps

Insulin pumps have an algorithm in them that can calculate the amount of bolus insulin needed based on your current BGL, your carbohydrate intake, your target BGL, your ISF, your ICR, and any insulin left on board (IOB). Talk to your healthcare professional if you think changes to this algorithm are needed.

A few words of caution

You should avoid taking extra injections, outside your pre-meal boluses, as this may lead to something called insulin stacking and can increase your risk of developing (severe) hypoglycaemia.

Calculating and using ISF only works if you are on a basal-bolus insulin regimen. It does not work if you are using pre-mixed insulins such as Humalog Mix25 or Mix50, Novomix, or Ryzodeg. If you are using a pre-mixed insulin talk to your healthcare professional for advice on insulin dose adjustments.

The above information is to be used as a guide only. Always follow the recommendations of your healthcare professional.

Insulin to Carbohydrate Ratio

If you like to vary your carbohydrate intake from one day to the next, you can use an insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio (ICR). This will help you get the right amount of insulin for the carbohydrates you will be eating.

What is the Insulin-to-Carbohydrate-Ratio?

The ICR means that you take 1 unit of rapid-acting insulin for a particular amount of carbs.

For example, if your ICR is 1:12 you would have to take 1 unit of rapid-acting insulin (either Apidra, Fiasp, Humalog, or Novorapid) for every 12 grams of carbohydrate eaten. If the meal contains 36 grams of carb and you have an ICR of 12 it would mean that you would need 3 units of rapid-acting insulin for this particular meal (36 : 12 = 3). Whereas a person with an ICR of 8 would need 4.5 units for the same amount of carbohydrates.

Your credentialled diabetes educator (CDE) or your endocrinologist can help you decide on what your ICR should be.

How is the ICR calculated?

You can calculate the ICR using the 500-rule.

First you need to calculate your Total Daily Dosage (TDD) by adding up both the rapid-acting (bolus or pre-meal insulin) and long-acting (basal or background) insulin doses in a 24-hour period. It will be more accurate if you calculate the TDD over a few days and take the average.

Then calculate the ICR by taking the number 500 and divide it by your current TDD.

For example: If you take 55 units of Optisulin at night and 8 units of Novorapid at breakfast, 6 units at lunch and 7 units at dinner your TDD will be:

55 + 8 + 6 + 7 = 76 units/day

500 : 76 = 6.6

This means that you will need 1 unit of rapid-acting insulin for 6.6 grams of carbohydrate. In other words, your ICR is 6.6.

Some healthcare professionals prefer to use the 450-Rule. This works the same as the examples above, except for using the number 450 instead of 500 in the calculations. Using the 450-Rule is a little more conservative. For example, if we use the case study above the calculation would be as follows:

55 + 8 + 6 + 7 = 76 units/day

450 : 76 = 5.9

This means that you will need 1 unit of rapid-acting insulin for 5.9 (or 6 to round it off nicely) grams of carbohydrate. In other words, your ICR is 6.0.

How do I use the ICR?

Work out how much carbohydrate you will have for your next meal and divide this amount by the ICR. For example: If you are going to have some pasta with a sauce and you calculate that this will contain 87 grams of carbs for the whole meal, you will need 13 units of rapid-acting insulin (if using the example above) as: 87 : 6.6 = 13.

It is easiest if you count your carbs in grams, rather than portions or exchanges. Talk to your dietitian for more information or consider attending the OzDafne program.

It is important to remember to bolus before the meal. In most cases 10-15 minutes before you start eating is ideal. Bolusing after the meal will see your glucose level rise a few hours later.

Taking insulin before eating and then not eating all of the planned carbohydrate may cause a hypo when the rapid-acting insulin peaks.

Another thing to consider is that fat and protein also have a role to play in glucose metabolism, find out more here.

Many people have different ICRs for different meals. For example: you may have an ICR of 10 for breakfast, 8 for lunch and 12 for dinner. If your snack size exceeds 30 grams of carbohydrate you may need to bolus for this snack to avoid glucose rises afterwards. Talk to your healthcare professional to see if

this applies to you.

How do I know if the ICR is correct?

To check if your ICR is correct you should check your BGL 2-3 hours after eating. If the BGL is 1-2 mmol/l higher than it was before the meal your ICR was spot on (and you estimated the carbs for that meal brilliantly).

If your after meal BGL is more than 3 mmol higher (or lower) than what it was before the meal, you need to consider making your carb ratio stronger by lowering the number (or weaker by increasing the number) or review your carb counting skills.

Rounding up or down?

In most cases you will have to round of the total amount of insulin to the next nearest full unit, unless you use an insulin pen device that can provide dosing in half unit increments. The question is: should you round up or down?

Well, this depends on your sensor glucose (SG) or blood glucose level (BGL) at the time. (If you are using continuous or flash glucose monitoring devices you should remember that for some devices a finger prick is required for insulin dosing – talk to your CDE for more details).

Generally speaking, if your BGL is high at the time it is usually recommended that you round up. But if your BGL is on the lower side it is worthwhile rounding down (and hopefully avert a hypo).

You should also consider what you will be doing during the following few hours. If you are going to be sitting around you may want to round up, but if you are planning physical activity you would do well rounding it down.

Check the basal first

Before calculating or changing the ICR it is important to check if your basal/background insulin (Toujeo, Semglee, Optisulin or Levemir) dose is correct. You can do this by comparing your pre-bed BGL with your fasting BGL. If your FBGL is often more than 4mmol higher or lower than the night before you may need to change your basal insulin dose by 1-2 units (follow the directions of your diabetes HCP).

Whenever the basal insulin dosage is changed it is advisable to give it at least 3 days to see the new pattern before making any further changes.

A few words of caution

In most cases you should avoid taking extra injections outside your pre-meal boluses, as this may lead to something called insulin stacking and can increase your risk of developing (severe) hypoglycaemia. However, as mentioned before, if your snack size exceeds 30 grams of carbohydrate you may need to bolus for this snack to avoid glucose rises afterwards. Talk to your healthcare professional to see if this applies to you.

Calculating and using ICR only works if you are on a basal-bolus insulin regimen. It does not work if you are using pre-mixed insulins such as Humalog Mix25 or Mix50, Novomix, or Ryzodeg. If you are using a pre-mixed insulin talk to your healthcare professional for advice on insulin dose adjustments.

The above information is to be used as a guide only. Always follow the recommendations of your healthcare professional.

Insulin on board (IOB)

Insulin on Board (IOB) refers to any insulin that is still active in your body from your last injection.

To understand how your IOB works, you will also need to know about the Active Insulin Time (AIT) or Duration of Insulin Action (DIA).

When you inject rapid-acting insulin, the insulin typically starts working within about 15 minutes, takes 1–2 hours to peak, and then continues to work in your body for 2–5 hours. Injecting more insulin during this time, and not considering IOB, can result in insulin stacking.

Knowing how much insulin is on board will help you get a more accurate insulin dosage, and will thereby improve your time in range.

Let us look at an example, to help make sense of this concept.

You are about to have a meal containing 45g of carbs. Your insulin to carb ratio is 1:15 and your insulin sensitivity factor is 2.5mmol/L. Your blood glucose level is 10.5, with a BG target of 5.5mmol/L. How much insulin do you estimate your pump would deliver?

If you said 5 units, you would be right. UNLESS you have any active insulin on board.

If your AIT is 4 hours, and your previous insulin injection was done 3 hours ago you will still have insulin on board. This will be deducted from the above amount.

Now, if you still had 2 units on board, then you will only need 3 units of insulin for this particular meal. If you would take the full 5 units you could be at risk of a hypo.

All current insulin pumps have an IOB feature. If this feature is activated, your pump will deduct any IOB from your bolus calculation. This means less risk of insulin stacking and it provides greater flexibility, as you can give more frequent boluses for snacks or as corrections, with less risk of hypos.

If you are using an insulin pump you can see if you have any insulin on board from your status screen. If you are on multiple daily injections (MDI) you could consider the use of an insulin bolus calculator

Calculating IOB

The way your pump calculates IOB, and how this is applied in bolus calculations can vary depending on the type of pump you have.

In some pumps IOB is only deducted from correction boluses, not the full meal bolus. This means that the full amount of IOB is not always deducted.

For example: if the correction bolus is 3 units and there are 2 units of IOB, the full 2 units are deducted. But if the correction bolus is 1 unit, only 1 of the 2 units of IOB will be deducted.

In other pumps both meal and correction boluses are considered when calculating IOB, but IOB is only deducted from correction bolus amounts if your glucose level is above target. If your BGL is below target the full amount of IOD is subtracted from the total bolus (including the food portion. This means that a small difference in BGL (just above versus just below the target BG) can result in very different bolus calculations. Let me explain with another example:

Your target BG is 7 mmol/l and your current reading is 10 mmol/l. Let’s say your total bolus is 7 units (5 for the meal + 2 for correction). Without any IOB, you would receive the full 7 units. But if you have 4 units of IOB, the correction bolus is reduced to zero, and the recommended dose would be just the 5 units for the meal.

But if your blood sugar is 5 mmol/l, and the usual dose is 4 units (5 for the food, -1 for the correction), the 4 units of IOB would be deducted from the 4-unit total, resulting in a recommended dose of zero.

And then there are some pumps that will only consider boluses that were given to correct high BGLs, when calculating IOB. These pumps assume that any insulin left from a meal bolus is covering any food that is still being digested from that previous meal. This leads to much lower IOB calculations than other pumps, and hence less bolus reduction (in other words more aggressive boluses, increased risk of hypos).

For example: if you gave 6 units for a meal and 2 units to cover an above-target reading, the 6 units is ignored in all IOB calculations in these types of pumps. Only the 2-unit correction portion is considered.

IOB and MDI

It is a little trickier to establish any active insulin if you are on multiple daily injections.

While it is possible to calculate IOB manually, it can be difficult and inconvenient. Luckily there are good apps that can assist you. Apps can range in functionality; some good options are:

- Accu-Chek®Connect app by Roche Diabetes Care Australia

- The mylifeTMApp by Ypsomed Australia

- The mySugr Bolus Calculator Appby Roche Diabetes Care Australia

All three of these apps are available in the App Store and on Google Play.

Target range

For a person who does not have diabetes, blood glucose levels (BGLs) will generally range between 4.0 and 7.8mmols/L throughout the day. This is regardless of how and what they eat, what exercise they do, or what stress they may be under.

If you are living with diabetes your body will have trouble keeping your BGLs within the “normal” range.

Target levels for people with diabetes will vary from person to person. It will depend on your age, how long you have lived with diabetes, any other medical issues you may have, and on the treatment that you are on to manage your diabetes.

Most people with type 1 diabetes are recommended to aim for fasting BGLs of 4-6mmol/L, before meals 4-7mmol/L and 2-3 hours after food 4-8mmol/L.

Most people with type 2 diabetes are recommended to aim for fasting BGLs of 4-7mmol/L, before meals 4-8mmol/L and 2-3 hours after food 5-10mmol/L.

In gestational diabetes much lower targets are recommended. This is because the foetus is very sensitive to glucose. If you have GDM you will, most likely, be advised to aim for fasting BGLs below 5mmol/L, 1 hour after meals less than 7.5mmol/L and/or 2 hours after meals less than 6.7mmol/L.

Despite your best efforts, you will find that your levels however, are frequently outside these target ranges. This is to be expected, as there are lots of reasons why your levels may go up or down. These include:

- The type and amount of food you ate, the time you had the food and how quickly you ate it

- Any planned and unplanned physical activity

- Stress, illness and pain

- Diabetes medicines you have taken

- Some other medications, such as steroids

- Hormonal changes

- Blood glucose monitoring technique or timing

It is normal for your BGLs to change throughout the day and night. The most important part of monitoring your glucose levels is to identify hypoglycaemia (low BGLs or hypo for short) and hyperglycaemia (high BGLs). High BGLs can increase your risk of long-term complications.

Discuss your readings with your health professional, so they can help you manage diabetes.

Active insulin time (AIT)

Active insulin time (AIT) refers to the time insulin remains working in your body. It is a safety feature mainly used in insulin pump therapy to help prevent over-correction of high glucose levels. Also known as Duration of Insulin Action (DIA), AIT is also used in bolus calculators to prevent insulin stacking (taking insulin injections too close together).

DIA or AIT can be set for a time up to 4.5 hours, however, in most cases, 3 hours is used.

Knowing how much insulin is on board will help you get a more accurate insulin dosage, and will thereby improve your time in range.

Let us look at an example, to help make sense of this concept.

You are about to have a meal containing 45g of carbs. Your insulin to carb ratio is 1:15 and your insulin sensitivity factor is 2.5mmol/L. Your blood glucose level is 10.5, with a BG target of 5.5mmol/L. How much insulin do you estimate your pump would deliver?

If you said 5 units, you would be right. UNLESS you have any active insulin on board. If your AIT is 4 hours, and your previous insulin injection was done 3 hours ago you will still have insulin on board. This will be deducted from the above amount.

Now, if you still had 2 units on board, then you will only need 3 units of insulin for this particular meal. If you would take the full 5 units you could be at risk of a hypo.

If you are using an insulin pump you can see if you have any insulin on board from your status screen. It is a little trickier to establish any active insulin if you are on multiple daily injections.